Back

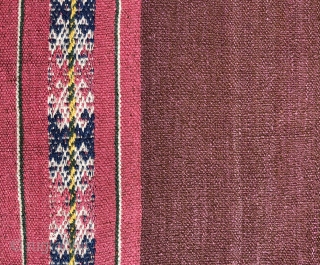

This fine warp faced weaving from the highlands of Bolivia was woven in the first half of the 19th century by Aymara Indians living at 12,500 ft. above sea level on the high Andean plateau known as the Altiplano. The Aymara are considered to be among the finest of all weavers in the Andes with a textile tradition that spans more than 2,000 years. After the conquest of the Americas by the Spanish in the 1500's the Aymara continued to weave using traditional dyes and fine alpaca fibers right up until the end of the 19th century. Their animals were specially bred over millenia for the finest, long staple fiber. The quality and length of their alpaca fibers allowed for super fine spinning and silky, lustrous yarns. All yarns used were two-ply yarns. Warp-face plain weave and various other complex /compound warp-faced weaving structures were the specialty of the Aymara. The textile shown here was made as a woman's mantle to be worn for ceremonial occasions. Known as aksu, these garments are a vestige of the original woman's dress form worn during the pre-Columbian period. Its use as a dress was outlawed by the Spanish sometime in the 16th century because of Catholic concerns over modesty and as a way to suppress the indigenous culture of the Aymara. Nonetheless, the aksu continued to be made after it was banned, but was worn as a large mantle rather than a dress and only for special occasions. The asymmetrical layout of the pattern bands and stripes seen in this piece is traditional. This textile features techniques that include the use of very finely spun two ply, bi-chrome yarns (chimi) which create a blended color field as seen in the details above. The reds and deep purple colors were made from cochineal and the blues are indigo. It is not certain what was used to produce the strong yellow color, but whatever it was, it resists fading unlike most other yellow dyes known. The green is a product of double dying yellow with indigo. Aymara textiles are remarkably finely woven. Because of this it is difficult to capture the amazing quality and sophisticated weaving and spinning in these pieces. Aymara textiles were never produced for the market place since style, designs and colors were distinct to the region, even the family, where they were made. Every area had its own distinctive patterning, colors and style. These textiles were woven exclusively as ceremonial textiles and to be worn as un-tailored articles of clothing. They were four selvedged and not cut from the loom. The protective finish work on the edges was a finely woven tubular edge finish known as a ribete. All these factors contribute to the stunning drape and handle of this old cloth. Among the Aymara the fineness of the alpaca fiber, the spinning and weave were universally understood and highly regarded by the weavers and non-weavers alike. The Aymara were a "textile-centric" culture, like no other in the Americas. Weaving was a sacred process, a integral part of life and revered in the culture. It was the primary art form of the Aymara indians. Weavings of this age and quality rarely survive it such fine condition. These textiles were used for centuries in some cases and passed down through the generations as the sacred cloth of the ancestors. As for many of us today, old textiles were considered by the Aymara to be more potent and magical than new textiles because they represented the ancestors. They were taken out of their sacred bundles for certain ceremonies and festivals and worn by participants as a way to reanimate their ancestors when worn and danced in rituals like the Day of the Dead. Size Approximately 55 x 48 inches.

price:

SOLD

- Home

- Antique Rugs by Region

- Category

- Profiles

- Post Items Free

- Albums

- Benaki Museum of Islamic Art

- Budapest: Ottoman Carpets

- Gulbenkian Museum

- Islamic Carpets. Brooklyn

- Islamic Textiles. Brooklyn

- Konya Museum: Rugs

- MKG, Hamburg

- MMA: Caucasian Carpets

- MMA: Mamluk Carpets

- MMA: Mughal Indian Carpets

- MMA: Ottoman Carpets

- MMA: Safavid Persian Carpets

- MMA: Turkmen Rugs

- McCoy Jones Kilims

- Ottoman textiles. Met

- Philadelphia Museum

- Rugs and Carpets: Berlin

- Seljuqs at the Met

- TIEM, Istanbul: Carpets

- V&A: Classical Carpets

- Vakiflar Carpets: Istanbul

- Baluch Rugs: Indianapolis

- Gallery Exhibitions

- Jaf an Exhibition

- Alberto Levi Gallery

- Andean Textile

- Christie's London: 2016

- Francesca Galloway

- HALI at 40

- ICOC Washington, DC 2018

- Jajims of the Shahsavan

- London Islamic Week April, 2018

- Mongolian Felts

- Navajo Rugs: JB Moore

- Persian Piled Weavings

- SF Tribal & Textile Art Show 2020

- SF Tribal 2019

- Sotheby's: C. Alexander

- Turkish Prayer Rugs

- Turkmen Main Carpets ICOC 2007